What can consumers do?

At Ethical Consumer, we have taken the view that avoiding palm oil altogether or choosing products with the very best sustainability certifications are both reasonable responses to a very complex set of issues.

Our product guides and palm oil ratings are designed to help people make this choice, whichever side of the line people personally fall.

We highlight companies which are palm oil free and those that are not, but get best marks for making some progress on the issue. We also incorporate into our ratings external criticisms, such as those from Greenpeace, of companies’ palm oil supply chains. The full details of how we arrive at the rankings appears on our website and, for logged-in subscribers, in the company stories that sit behind the table scores.

The sense of urgency is increasing. A report from Changing Markets published in April 2018 has cast further doubt on the ability of certification schemes, such as the RSPO, to help.

However, the key campaigners in this field – Greenpeace included – are not arguing for a consumer boycott of all palm oil. It is recognised that pressure from western consumer markets is at least driving some environmental standards into the industry but lots of growth is coming from markets – like those in China and India – without similar demands for environmental standards.

Of course, the growing use of palm oil is also heavily linked to the increase in the amount of processed foods consumed in the west. Cooking fresh meals can have multiple benefits such as avoiding fat, sugar, salt as well as palm oil.

In addition, it is always worth keeping up with the name-and-shame campaigns from the big campaigners like Greenpeace and SumOfUs. Strategically avoiding the worst companies out there will help create pressure in the right place in the short term, and it certainly makes sense to focus on the companies with the biggest market power. Unilever, for example, uses over 1 million tonnes annually and, therefore, its power to affect change is far greater than a company using less.

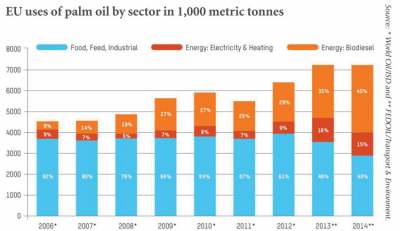

And finally, acting as citizens as well as consumers is important too. Keeping up the pressure to remove palm oil from, for example, transport biofuels will be a key part of any plan to halt the destruction associated with this most troublesome of crops.