Trainers have become status symbols in popular culture as much as practical items, with some trainers selling for millions at prestigious auctions like rare artworks.

Over 20 billion shoes are produced annually worldwide with around 300m pairs of trainers alone thrown out every year, which are mostly made from problematic and complex combinations of materials that barely degrade.

Ultimately, we need fewer trainers in the world. But while some trainers are an "affordable luxury treat" and trainer company profits continue to rise, what does buying an ethical trainer look like?

What are ethical trainers?

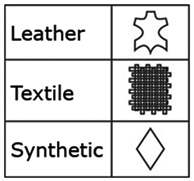

To find ethical trainers we looked at the materials used to make trainers, including use of animal leather, synthetic materials and plant based vegan options. We also looked at workers' rights and supply chain issues, and whether you can recycle or repair your trainers.

This guide features the biggest names in trainer footwear like Nike and Adidas, alongside secondhand retailers and small specialist vegan and vegetarian brands.

Unsurprisingly, some brands score very badly, with over half the brands scoring under 25 points (out of 100). However, there are some high scoring ethical brands available.

Read on to find out where your favourite brand comes in our guide to ethical trainers.

NB: We know that the sale of Depop by Etsy to Ebay has been agreed by their boards but until regulatory approval has been received (April-June 2026) we have left Depop with its current owner, Etsy. The sale will likely make very little difference to Depop's score because Ebay and Etsy have similar scores.