Over the last few decades, soya has driven huge deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, particularly in Brazil. It is linked to massive loss of biodiversity, high carbon emissions and the violations of indigenous rights.

Soya has long been eaten by people around the world, and has more recently become an important part of vegetarian and vegan diets including in the UK.

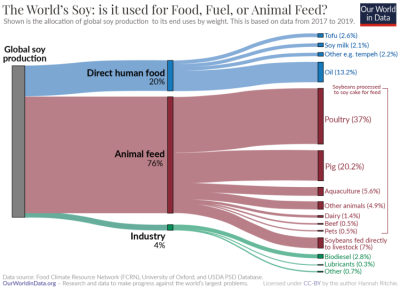

However, the vast majority of soya is used for animal feed – making meat and dairy the hidden drivers of soya-related harms.

Soya and deforestation

The largest soya-producing countries are the US, Brazil and Argentina, which together produce about 80% of the world’s supply. Soya is Brazil’s second biggest export by value, and there have long been serious concerns about the extent to which it is behind deforestation in the Amazon and surrounding regions.

To date, around 17 percent of the Amazon has been lost. Vast areas have been chopped down to make space for agricultural land, used for growing maize and soya and rearing cattle.

As a result, the rainforest stores around 30 percent less carbon than it did in the 1990s.

Land grabs for farming endanger Indigenous People. Indigenous communities can be displaced from their Territories and face violence. Indigenous People defending the environment can be attacked or even killed.

Scientists warn that once deforestation reaches 20-25 percent of the total, the rainforest will reach a ‘tipping point’. Human activity will have pushed it to a point where the natural cycles break down: the processes trees use to draw water up from the earth and create rain in the atmosphere will no longer function and will be irreversibly destroyed.

Politicians, NGOs and corporations have made efforts to reduce the impacts of soya on deforestation. However, in 2020, an academic paper estimated that as much as 20 percent of soya exported from Brazil’s largest carbon sinks to the EU was still tainted with deforestation.