In the UK we consume clothing faster than any other country in Europe and produce around 206.456 tonnes of textile waste in a year, making us the fourth largest textile waste producer in the continent.

This article looks at 10 simple ways you can move away from fast fashion and help reduce the impact on the environment.

1. Make a second-hand pledge. Buy only second-hand for a year.

Producing new clothing has a significant carbon footprint: just one new pair of jeans is equivalent to driving 50 miles. Extending the lifecycle of an item of clothes by even just an extra nine months can reduce the relative carbon, water and waste impacts of that garment by 20-30%.

A second-hand pledge can be a good way to make yourself commit to no new clothing for a length of time. Extinction Rebellion is asking people not to buy any new clothes for a year. TRAID encourages people to take its #Secondhandfirst pledge and commit to sourcing a chosen percentage of their wardrobe second-hand rather than buying new.

2. Upcycle

On average, each person throws away eight items of clothing every year. In 2018, this added up to 300,000 tonnes of textiles just from the UK - which is equivalent to the weight of almost 30 Eiffel towers.

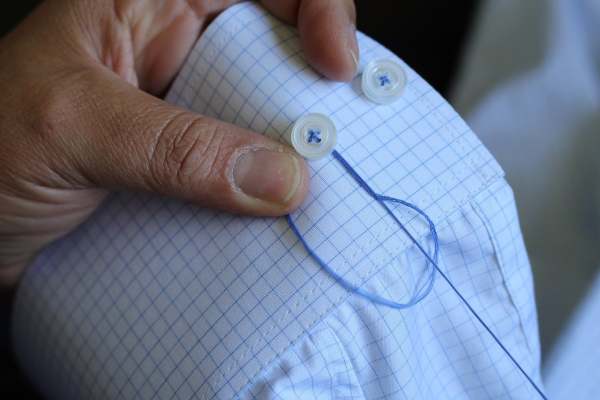

Instead of throwing clothes away, you could adapt them. Or buy second-hand and alter them to fit you. For example, if you’re hesitant to buy items like jeans second-hand because you’re worried about getting the right fit, buy a pair that you know will be a bit too big and use an online tutorial to downsize them.

The Love Your Clothes website has lots of great information on upcycling and repairs.

3. Make a Pinterest board but only include looks that you can create with clothes you own already.

Sustainable fashion influencer Aja Barber said her biggest tip for learning to love your existing clothes “is to find your personal style.”

The Project Cece ethical fashion website suggests asking yourself before you buy whether you will wear a piece of clothing 50 times. If not, don’t buy it.