Finding ethically sourced chocolate

This guide covers a range of issues linked to sustainability and the cocoa supply chain including child labour on cocoa farms, fair trade, deforestation, pesticide use, and cocoa sourcing policies. We also look at issues related to other ingredients often found in chocolate, namely palm oil and dairy milk.

Chocolate brands in this guide

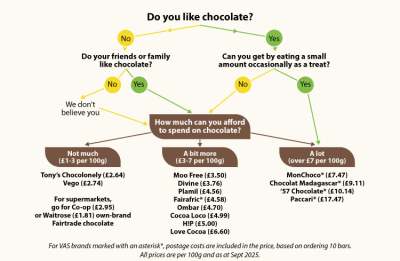

We have covered the major mega chocolate producers, smaller, alternative companies making vegan and organic chocolate, and five tree-to-bar (also known as value-added-at-source) companies making chocolate bars in cocoa-growing countries so that more wealth stays in the origin country.

Cadbury is by far the most popular chocolate brand in the UK, made by the world’s biggest chocolate company, Mondelēz.

Ferrero, Lindt, Mars, Mondelēz and Nestlé dominate the UK chocolate market, accounting for just over half of chocolate sold in the UK. These are the same five companies that fall into the “poor” section of the scoretable, all scoring under 25/100 overall.

We've include all these 'big five' companies, along with some of their acquired brands like Hotel Chocolate (owned by Mars), Green & Blacks (owned by Cadbury / Mondelēz), Thorntons (owned by Ferrero), plus brands like Ritter Sport and Guylian.

The guide also includes several widely available smaller brands like Booja Booja, Divine, Montezuma's, Tony's Chocolonely, and Oxfam, along with brands like Moo Free, Ombar and Vego and less well-known brands like Fairafric, MonChoco and Paccari.

We primarily looked at solid bars of chocolate but many of the companies also make chocolate snack bars and boxes of chocolates.

New to this guide is a section on hot chocolate, cocoa and chocolate spread.