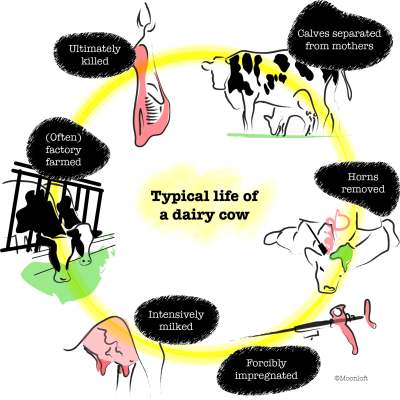

Issue 5: Often factory farmed

Many cows have only limited, or no, access to grazing in the outdoors. Our feature on dairy milk certification schemes discusses which milk products are more likely to come from cows that have access to grazing.

A 2014 study found that just 31% of dairy farmers in the UK practised summer grazing and winter housing, with the remaining farmers moving cows indoors for even more of the year, and 16% keeping some or all cows inside for the whole year.

In 2018 an estimated 23% of UK and Ireland farms kept some or all of their cows inside for the whole year.

Intensive factory farming of dairy cows happens in the UK. A 2015 article in The Independent for example featured a mega-dairy which homed at least 1,300 cows, who were not permitted to graze in the fields that surrounded the farm and instead were kept inside.

Another example is major milk producer Grosvenor Farms Ltd which has a 2,600 herd. We viewed its website in November 2021 and it appeared that the cows are seemingly only permitted to roam inside their barns, which the company describes as “larger than typical industry standards”. In 2019 director Mark Roach stated “we have recorded an average 14 hours lying time which equates to the behaviour of a grazing cow” which also suggests the cows are not able to graze.

Following Brexit the dairy industry is facing shortages of labour, as many dairy farm workers were foreign workers. This leaves dairy farmers under more stress and pressure when supermarkets and large dairy companies are already demanding milk at astonishingly low prices. This increases the pressure on farmers to keep cows indoors because it is cheaper than permitting cows to roam.

Issue 6: Dairy cows are ultimately killed

After a cow first calves at around aged two, in developed dairy industries they will usually go on to produce milk for between 2.5 to 4 years. This brings their total lifespan from birth to death to between 4.5 to 6 years. If higher welfare standards are maintained, the cow might be able to produce milk for slightly longer periods and thus live longer.

The natural life expectancy of dairy cows is 20 years.

If a cow is unable to conceive quickly enough, becomes unhealthy and injured, or doesn’t yield much milk they might be culled.