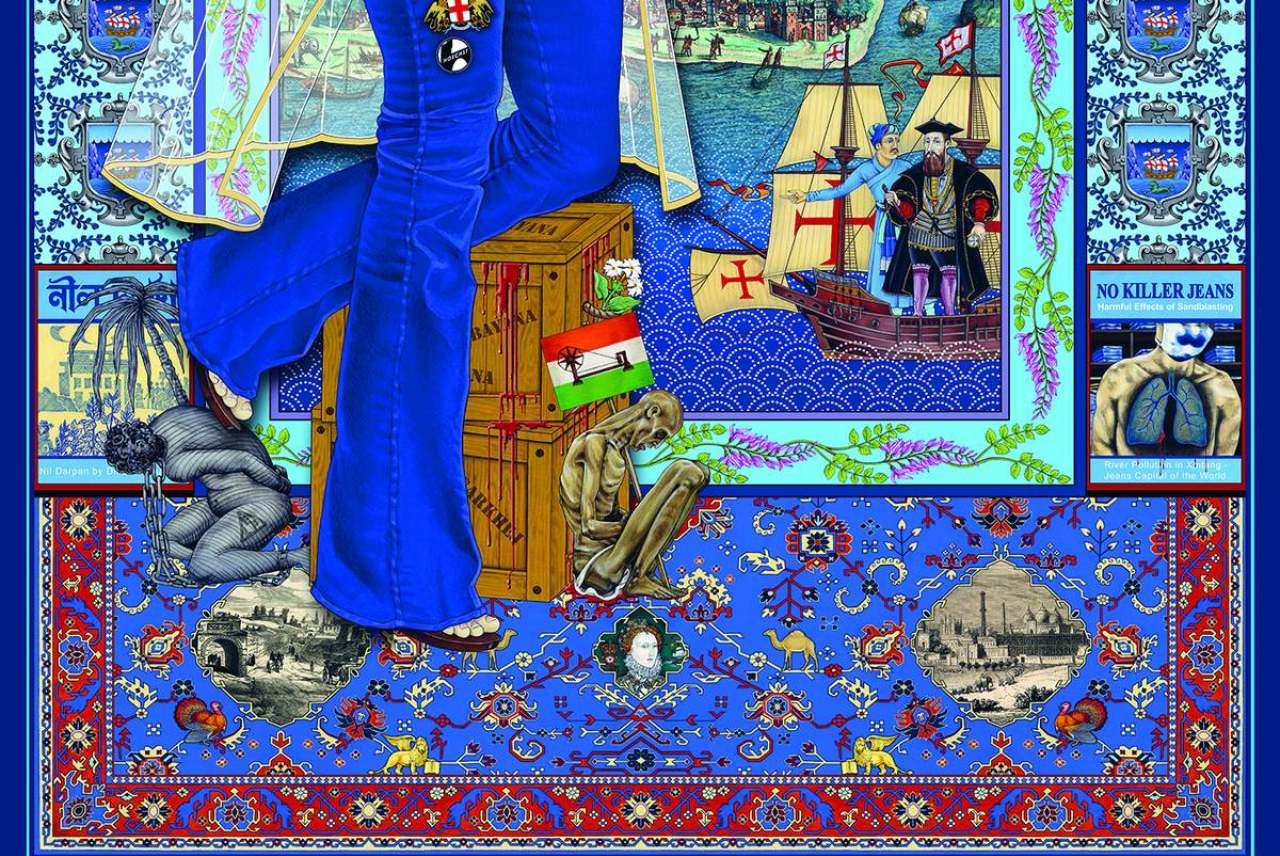

This artwork explores stories around the blue dye extracted from the leaves of the Indigo plant. It is believed to have originated in India, where it has been used for thousands of years.

Indigo dye and textiles became highly desired across the globe – from the Far East and Africa to Europe, North America and the West Indies. Determined to seize control of the market, knowledge about how to cultivate Indigo was eagerly sought by European traders.

The artwork depicts the 17th-century Indian queen, Mumtaz Mahal, wife of Emperor Shah Jahan (depicted in her pendant) who placed the monopoly on the trade of Indigo.

She wears blue denim jeans commonly associated with modern western fashion and values. She thereby presents a challenge to this perception regarding the cultural ownership of denim fabric – the true origins of which go back to 16th century India, in the port town of Dongri where this tough fabric was used for sails and ‘dungri’ (later ‘dungarees’) worn by sailors.

Bedecked with jewels, Mumtaz also represents the fact that Indigo dye was once rare and very expensive – a luxury commodity associated with royalty, political power and authority. Known as ‘blue gold’ it was so valuable that, when prices were high, it was used as currency to purchase slaves who were worth their own weight in indigo.

The Taj Mahal (depicted in the vignette top right) was built in Mumtaz’s memory at Agra, India. This city was a main centre for production of highquality indigo known as ‘Bayana, or ‘Agra’ indigo which was most sought after in the West.

Another high-quality indigo was ‘Sarkej’ which was produced in the city of Ahmedabad which is represented by the gateway to one of its famous landmarks (‘Shah-e-Alam Roza’) seen in front of the Taj Mahal. To the left, the Marigold and Flame of the Forest flowers represent the Indian States of Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh in which Ahmedabad and Agra are situated respectively.