Three years before the COVID-19 pandemic, it was clear even to capitalism’s biggest cheerleaders, the World Economic Forum, that “the global economy is broken”.

With the climate crisis spinning out of control and ever rising inequality, the idea that the single-minded pursuit of profit by unregulated global business will somehow lead to better outcomes for everyone is now, quite rightly, filed under ‘tried and proven not to work’.

Unfortunately, there do not currently appear to be any global institutions capable and ready to step in to fix things. This means we face the daunting task of trying to persuade the institutions we do have to change direction quickly.

Banks and the web of unethical business

Banks and other financial institutions will play a particularly important role because they sit at the heart of the broken global economy. The decisions they take daily – on which projects to finance or not – determine the direction of travel for this economy and therefore for us all.

In June of this year, for example, a report by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Unearthed found that British-based banks and finance houses had provided more than $2 billion in financial backing to Brazilian beef companies linked to Amazon deforestation.

Perhaps this made sense to the banks based on immediate financial return on investment. Yet, when balanced against the scientifically agreed actions needed to preserve a global ecosystem and allow Homo sapiens as a species to thrive, it looks less smart.

That many people now understand the central role of banking has been shown by recent Extinction Rebellion protests. For example, in October 2019, dozens of XR protesters were arrested for demonstrating outside the Bank of England. Hundreds of protestors sat down in the road outside the bank in a protest against “the system bankrolling the environmental crisis”.

Civil society rising

Campaign groups have, of course, long been concerned about the impacts that banks make, from the boycotts of Barclays over its support for racism in South Africa in the 1970s to modern-day campaigners against deforestation.

In 2020, the list of reports and analyses published by civil society criticising banks appears to be longer than ever. We have highlighted some of these in the our ethical money pages:

- Banks and the environmental crisis

- Campaigning against Barclays and the Rampal Coal Power Plant in Bangladesh

- High pay in the financial sector

- The gender and ethnic minority pay gap in the banking sector

- Banks profiting from the arms trade

- Banks’ historical links to the slave trade

- What's wrong with Barclays and HSBC?

- Deadly investments in Israel

- Banks and animal exploitation

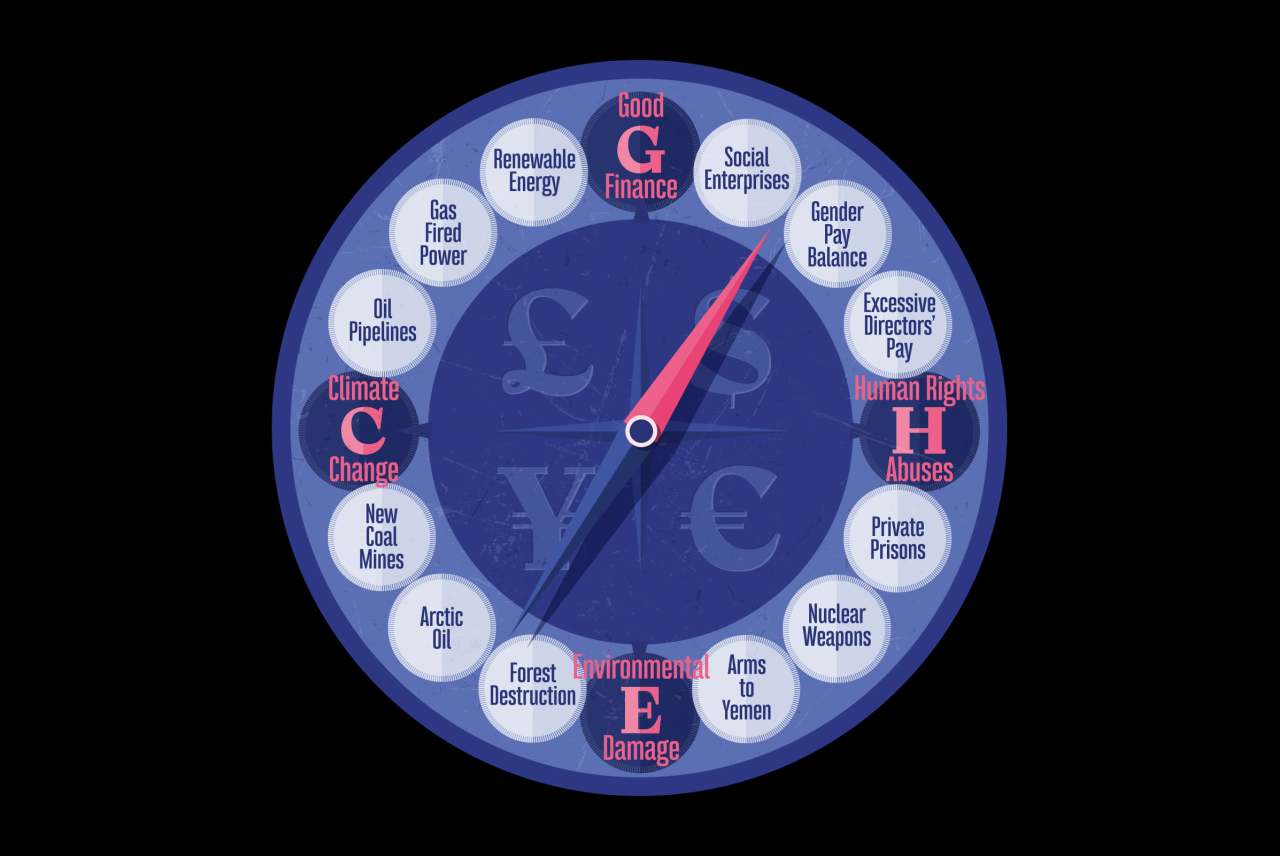

We have also listed some of the issues on our ‘moral compass’ image featured above as another way of illustrating the choices that bankers are currently making.

The role of consumer choices

Whenever Ethical Consumer is approached by journalists asking about the top five or ten ethical choices that consumers can make, changing bank accounts is almost always on the list.

This is because, although your own savings might not be that great, the place of most banks at the centre of the web of business means that the choices you make can become amplified across the economy. When choosing a bank, you are in a sense choosing how you want the whole economy to look.

A glance at the average savings of UK adults shows not just how unequal our society is but how this amplification might work. Figures vary, but we know that roughly:

- 9% have no savings at all.

- One third have less than £600 in savings.

- Average UK savings are £9,633.

- Men have almost double (£13,140) the average savings of women (£6,869).

- Londoners have the highest average savings with £28,978.