Banking is a bust flush, manufacturing is languishing and all our companies are either dodging taxes or being sold off overseas. It is about time we woke up as a nation and smelled the freshly brewed Fairtrade coffee. When it comes to the economy, either we can wait to be dragged down or we can get on and do it ourselves.

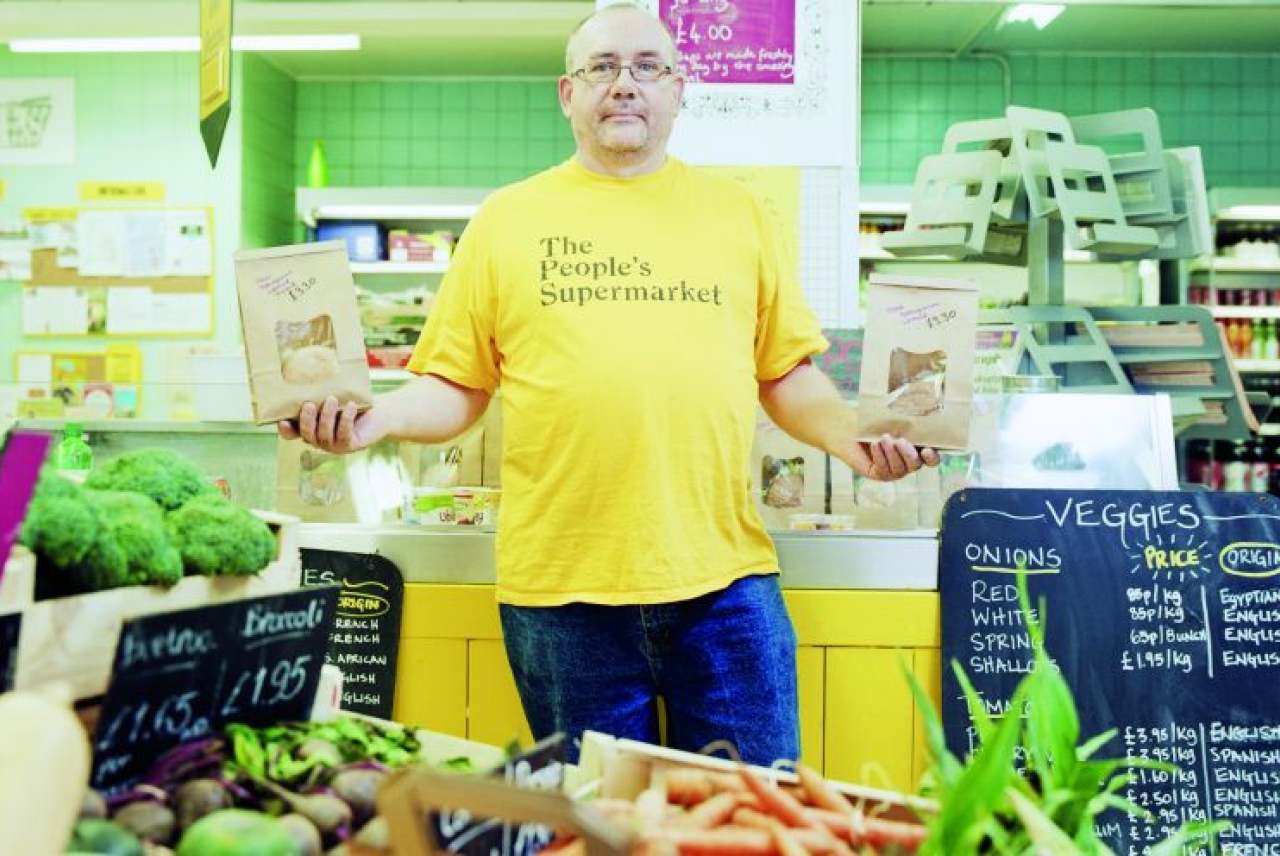

In one corner of central London, local people are doing just that. A community has come together and created the People’s Supermarket as a co-operative business, which is owned and run by the members who shop there. It has been hard work for those involved but the result is that local residents have their own shop, stocking what they want and selling it at competitive prices to local people. Echoing the success of the first, early Victorian co-operative pioneers in Rochdale, this is self help and mutual aid for a post credit crunch Britain.

The People’s Economy

Arthur Potts Dawson of the People’s Supermarket and Ed Mayo of Co-operatives UK explain today’s resurgence of interest in co-operatives.

How did it happen?

The idea of setting up a business in the same market as Tesco and ASDA might seem crazy to most people. But that mindset is why we don’t have new upermarkets on the high street, why we don’t have new banks or new energy companies.

Supermarkets are good at hoovering up people’s money and forcing producer prices down in the field. What they are poor at is getting people to connect to each other, either in a community or across the food chain. This destabilises communication and interaction within society, which has always been essential for villages, towns and cities if not for any other reason than for their own identity. Now with the financial troubles that everyday people find themselves in, the last thing that their neighbourhood needs is a supermarket that kills the local economy, sucks out the peoples identity and forces a monoculture buying system on them.

Structure

The model that the People’s Supermarket is based on is a food co-operative from Brooklyn, New York, The Park Slope Food Coop, which has had long-run success, combining organic food and volunteer staff. Here, members pay £25 to join and commit to four hours a month helping to run the shop. As member/owners, they get cheaper prices and good, affordable food.

The result is a community feel, unlike any other, coupled with a loyalty and an insight into what customers want that marketing directors in mainstream companies can only dream of.

It is not a John Lewis model and nor is it a traditional consumer co-operative, as it is the same people who work and shop there that are the owners. But in true democratic style, the co-operative is based on one member, one vote rather than the shareholder model of one pound, one vote. Food co-operatives of this kind are on the rise right across the UK, with around four hundred initiatives, helping people to save money, source local produce or eat healthily. They are starting to reconnect a food chain that was thought to be lost to the big multiples, by striking deals with farmers and promoting awareness of local food and co-operative action.

More widely, the co-operative model is in a period of renaissance, with 12.9 million members across the UK, from village shops to credit unions. With a ‘peak oil’ scenario of high oil prices and dwindling supplies seeming ever more real, for example, other bootstrap, co-operative businesses are emerging to encourage local production of energy. Battling both climate change and the planning system, co-operative windfarms are helping to get local people on board with renewable energy, because the benefits are shared with them rather than passed onto the big corporate energy utility barons.

Elsewhere

In Denmark, co-operatives like these have made their country a world leader in renewable energy, helping to create the world’s largest turbine industry. The equivalent of just under a third of Denmark’s electricity now comes from renewable energy. In tough times, the principle of relying on distant corporations to sell us food, make us coffee and produce our energy is a luxury we can’t afford. The people’s economy has a different way of looking at enterprise – which is that if the people who contribute to the success of a business, also benefit from it, both business and people benefit.

As a nation, we have become passive, enjoying a sense of entitlement, which turns out to have been based on cheap oil, cheap credit and government and business IOUs. We need a do it yourself mindset to get going again and a do it yourself economy which recreates a very long British tradition of self help and mutual aid.

Arthur Potts Dawson is co-founder of the People’s Supermarket

Ed Mayo is Secretary General of Co-operatives UK

Also see our ethical guide to supermarkets.

Become a subscriber today

Ethics made easy - comprehensive, simple to use, transparent and reliable ethical rankings. A wealth of data at your fingertips.

From only £34.50 for 12 months web access and the print magazine. Cancel via phone or email within 30 days for a full, no-questions-asked refund!