Putting pressure on governments and oppressive regimes

At Ethical Consumer we mostly focus on corporate activity and try to leverage brand power to improve conditions for people, the planet and other animals.

But sometimes our consumer spending can play a role in holding governments to account, too, especially through whole country boycotts.

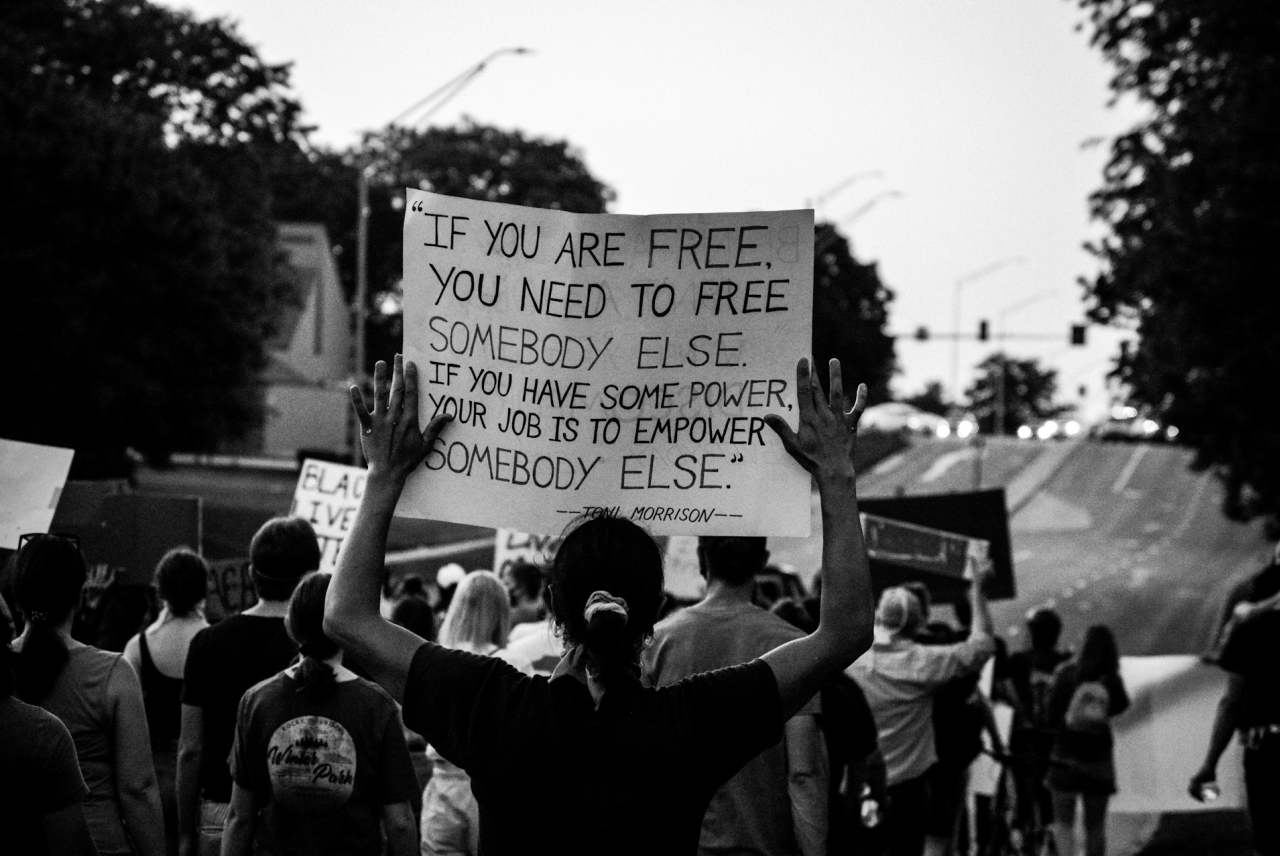

These have long been one of the few tools available to ordinary people when states commit grave abuses and international institutions fail to act – a form of international pressure where diplomacy falters.

Country-wide boycotts

From apartheid South Africa to present-day Israel, Russia and Myanmar, refusing to trade or consume has been a way of confronting state violence directly.

By cutting off profits, consumer action disrupts the economic lifelines that authoritarian regimes depend on, and makes it clear that repression carries a cost on the world stage. In this sense, boycotts transform everyday spending into a tool of accountability, linking the supermarket aisle to the struggle for justice across borders.