What does net zero mean for the world?

Greenhouse gases are emitted through human activities such as the burning of fossil fuels. But they are also absorbed from the atmosphere through what are known as 'carbon sinks' - for example plants that absorb carbon dioxide as they grow, and the oceans that absorb it as it gets mixed into the water.

‘Net zero’ for the world means that the greenhouse gases emitted are balanced by carbon sinks. We can enhance these sinks by restoring forests, peatlands and mangroves.

We can also suck carbon out of the air by growing plants, capturing the CO2 and then burying it, which is called biomass with carbon capture and storage (BACCS), or by capturing it directly from the air and burying it (DACCS). These are known as 'net negatives' - because they remove more carbon than they emit.

'Net negatives' are controversial, particularly as they generally take up a lot of land, and the planet is currently a little rammed. However, all government scenarios under the COP 21 Paris Agreements, which show how we may be able to limit the planet to a 1.5°C temperature rise, see them playing a major role. Their capacity is very limited though – they can only be used to mop up the dregs.

Limiting global warming to 1.5°C requires reducing emissions by about 90% by 2050 from 2010 levels. The remaining emissions, in the sectors which are hardest to tackle, will have to be neutralised with such net negatives in order to take us to zero. Then towards the end of the century we will need to go into negative emissions as a globe to suck out the overshoot.

Carbon neutral is not net zero

Although they have no fixed meanings, the terms ‘net zero’ and ‘carbon neutral’ are generally used quite differently. It’s easiest to understand the essence of how ‘carbon neutral’ is mostly used if you view it as not so much neutral for the climate, but neutral in terms of either tackling climate change or not. It is as if someone says “do you think we ought to tackle climate change?” and you reply “I’m neutral on it”.

This is because ‘carbon neutral’ basically compares to the current business-as-usual scenario, rather than to where we need to be. It refers to a specific product or process at a specific snapshot in time, and it means that any emissions associated with it have been ‘neutralised’, which often means paying someone else to reduce their emissions by an equivalent amount.

But this is just passing the buck onto someone else, which doesn’t work when they need to be reducing their own emissions already – we all have to be wrestling with that buck.

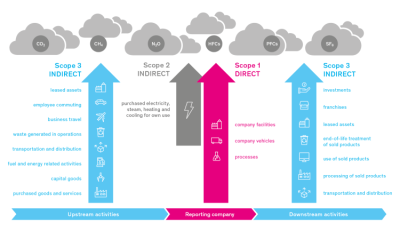

Additionally, ‘carbon neutral’, as defined by the PAS 2060 international standard, only needs to cover scope 1 and 2 emissions. So it doesn't cover emissions from the company's supply chains or its products' use, which are likely to be by far the greatest bit (see definitions below).

In summary: carbon neutral is for scoundrels.