At a global level, about 24-30% of tea grown is certified Fairtrade, Organic, Rainforest Alliance (including UTZ), with Rainforest Alliance by far the most widespread tea certification.

About 55% of coffee grown is certified.

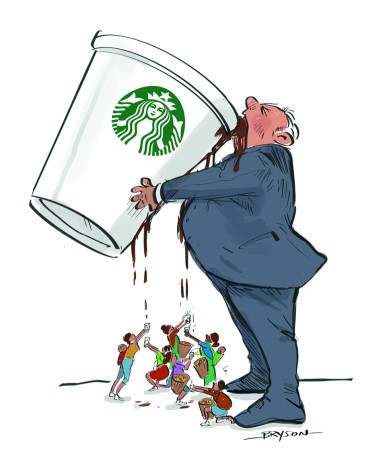

However, for both tea and coffee, only a fraction of the amount which is grown to certification standards is sold on those terms. The Coffee Barometer report by Solidaridad, Ethos Agriculture, and Conservation International argues that more action is needed by the industry to properly market certified options, giving producers the support they deserve.

In this article we look at the main certification schemes available to producers and the difference between them.

Fairtrade

Fair trade isn’t a protected term (unlike organic) so you have to be careful – those certified by the Fairtrade International standard will be written as a single capitalised word (Fairtrade) and carry the symbol that looks a bit like the yin/yang symbol. (It is in fact a person with an arm raised, if you look at the black shape.)