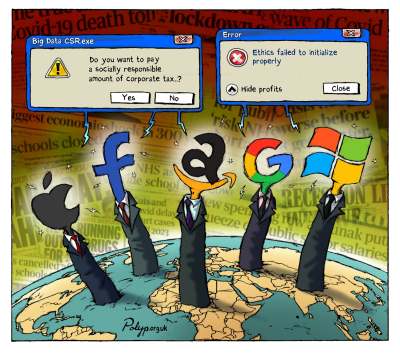

Big Tech companies like Google, Amazon and Facebook have avoided paying proper taxes on their profits in every country in the world for many years now. Like wayward children focused on fun and games, every time a government introduces new rules to try to stop tax avoidance happening, they find another loophole or trick to escape capture.

For the rest of us, it’s long since stopped being funny. With the pandemic particularly, government resources to help the poor and vulnerable are running short. The spectacle of giant corporations, who thrive on our social isolation, experiencing extraordinary economic success at the same time, means that voices clamouring to close the gap now come from across the political spectrum.

But how actually do you stop it happening, even if you want to?

The problem has been causing sleepless nights for clever people for nearly a decade now and has led to at least three rounds of initiatives.

Round One – International Agreements

Multilateral institutions like the OECD have been building complex new rules to prevent ‘profit shifting’ by multinational companies since 2012. And although this has met with some success, finding agreement on how to tax the new digital economy remains bogged down. Opposition from the US government has been key to this lack of progress.

Because of this impasse, national governments have become impatient and started introducing their own rules.

Round Two – Diverted Profits

Tax In the UK, following pressure from all parties, the then Chancellor Philip Hammond introduced a diverted profits tax in 2015 aimed at multinational corporations, both digital and otherwise.

Although, in January 2020, the UK government announced that it had secured a significant additional £5 billion of tax, much continues to be avoided by Big Tech companies particularly.

Round Three – Digital Service Tax (DST)

In the UK in April 2020, a digital services tax went into effect at a rate of 2% on all UK sales of very large companies providing search engines, social media services and online marketplaces. This approach, of a tax on sales rather than profits, has now caught on globally in various forms and, at the last count, 36 countries have implemented or announced plans for such a tax.

Round Four – A pandemic windfall tax?

As we have explained in previous articles, when you look at the rates of Digital Sales Taxes (DSTs) in other countries, it appears that the UK’s rate is relatively modest. In Turkey it is set at 7.5%, in the Czech Republic 7% and in Austria it is 5%.

In July this year, we proposed increasing the DST to 10% during the pandemic in order to help finance the very costly social and health interventions the pandemic has required. This kind of approach has been suggested elsewhere too since then with, for example, Tom Kibasi writing in the Guardian suggesting that a rebalancing “could be accomplished through a special levy – calculated as a percentage of UK sales – for the decade ahead.”

At Ethical Consumer we have been working on a campaign for a windfall tax for big tech companies.